Conway's Law [Framework of the Day]

Conway's Law explores the connection between organizational structure and system design, providing insight into the impact of company architecture on innovation and offering potential strategies for handling mirrored product design.

Thanks again for reading and for all the positive feedback. Please keep it coming. If you haven't read any of these yet, the gist is that I'm writing a book about mental models and writing these notes up as I go. You can find links at the bottom to the other frameworks I've written. If you haven't already, please subscribe to the email and share these posts with anyone you think might enjoy them. I really appreciate it.

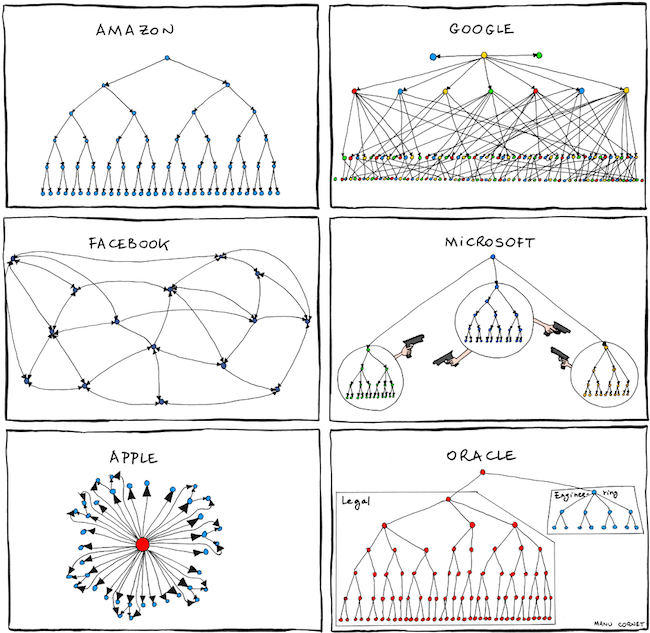

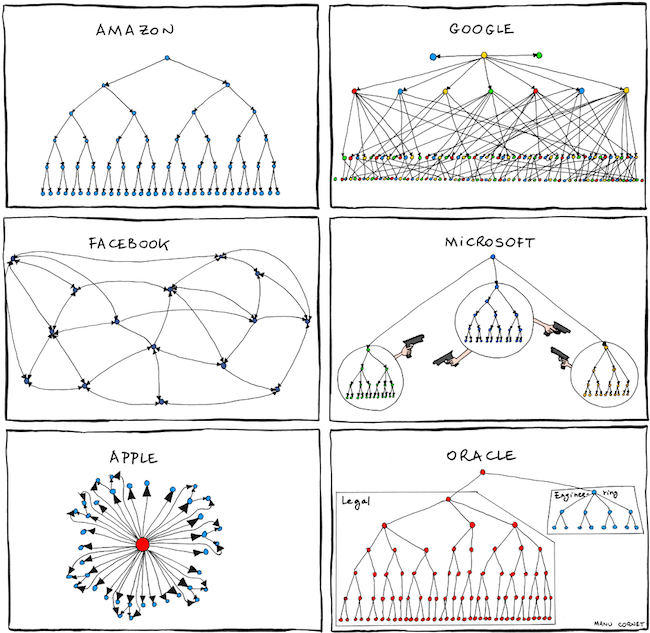

Credit: Organizational Charts by Manu CornetI first ran into Conway's Law while helping a brand redesign their website. The client, a large consumer electronics company, was insistent that the navigation must offer three options: Shop, Learn, and Support. I valiantly tried to convince them that nobody shopping on the web, or anywhere else, thought about the distinction between shopping and learning, but they remained steadfast in their insistence. What I eventually came to understand is that their stance wasn't born out of customer need or insight, but rather their own organizational chart, which shockingly included a sales department, a marketing department, and a support department.

"Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." That's the way computer scientist and software engineer Melvin Conway put it in a 1968 paper titled "How Do Committees Invent?" His point was that the choices we make before start designing any system most often fundamentally shapes the final output.1 Or, as he put it, "the very act of organizing a design team means that certain design decisions have already been made."

Why does this happen, where does it happen, and what can we do about it? That's the goal of this essay, but before I get there we've got to take a short sojourn into the history of the concept. As I mentioned, the idea in its current form came from Melvin Conway in May of 1968. In the article he cited a few key sources as inspiration including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and historian C. Northcote Parkinson, who's 1957 book Parkinson's Law and Other Studies in Administration was particularly influential in spelling out the ever-increasing complexity that any bureaucratic organization will create.2 Finally, judging by the focus on modularity in Conway's writing, it seems clear he was also inspired by Herbert Simon's work, in particular his "Architecture of Complexity" paper and the Parable of Two Watchmakers (which I wrote about earlier).

Parkinson aside (who did so mostly in jest), very few have the chutzpah to actually name a law after themselves and Conway wasn't responsible for the law's coining. That came a few months after the "Committees" article was published from a fan and fellow computer scientist George Mealy. In his paper for the July 1968 National Symposium on Modular Programming (which I seem to be one of the very few people to have actually tracked down), Mealy examined four bits of "conventional wisdom" that surrounded the development of software systems at the time. Number four came directly from Conway: "Systems resemble the organizations that produced them." The naming comes 3 pages in:

Credit: Organizational Charts by Manu CornetI first ran into Conway's Law while helping a brand redesign their website. The client, a large consumer electronics company, was insistent that the navigation must offer three options: Shop, Learn, and Support. I valiantly tried to convince them that nobody shopping on the web, or anywhere else, thought about the distinction between shopping and learning, but they remained steadfast in their insistence. What I eventually came to understand is that their stance wasn't born out of customer need or insight, but rather their own organizational chart, which shockingly included a sales department, a marketing department, and a support department.

"Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." That's the way computer scientist and software engineer Melvin Conway put it in a 1968 paper titled "How Do Committees Invent?" His point was that the choices we make before start designing any system most often fundamentally shapes the final output.1 Or, as he put it, "the very act of organizing a design team means that certain design decisions have already been made."

Why does this happen, where does it happen, and what can we do about it? That's the goal of this essay, but before I get there we've got to take a short sojourn into the history of the concept. As I mentioned, the idea in its current form came from Melvin Conway in May of 1968. In the article he cited a few key sources as inspiration including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and historian C. Northcote Parkinson, who's 1957 book Parkinson's Law and Other Studies in Administration was particularly influential in spelling out the ever-increasing complexity that any bureaucratic organization will create.2 Finally, judging by the focus on modularity in Conway's writing, it seems clear he was also inspired by Herbert Simon's work, in particular his "Architecture of Complexity" paper and the Parable of Two Watchmakers (which I wrote about earlier).

Parkinson aside (who did so mostly in jest), very few have the chutzpah to actually name a law after themselves and Conway wasn't responsible for the law's coining. That came a few months after the "Committees" article was published from a fan and fellow computer scientist George Mealy. In his paper for the July 1968 National Symposium on Modular Programming (which I seem to be one of the very few people to have actually tracked down), Mealy examined four bits of "conventional wisdom" that surrounded the development of software systems at the time. Number four came directly from Conway: "Systems resemble the organizations that produced them." The naming comes 3 pages in:

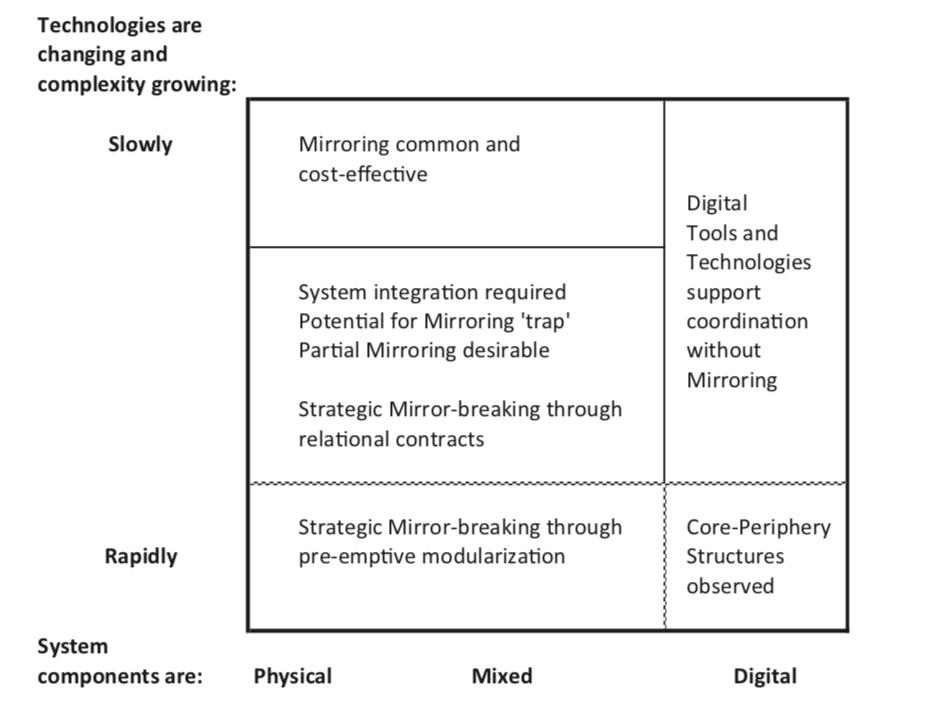

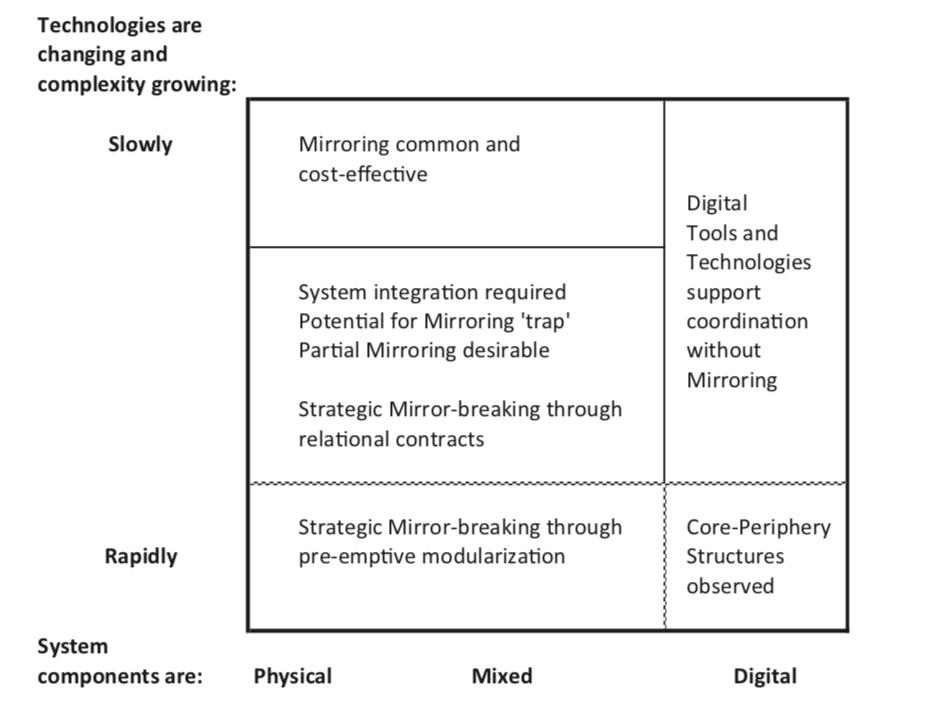

As you see at the bottom of the framework you have option three: "Strategic mirror-breaking." This is also sometimes called an "inverse Conway maneuver" in software engineering circles: An approach where you actually adjust your organizational model in order to change the way your systems are architected.5 Basically you attempt to outline the type of system design you want (most of the time it's about more modularity) and you back into an org structure that looks like that.

In case it seems like all this might be academic, the architecture of organizations has been shown to have a fundamental on the company's ability to innovate. Tim Harford recently wrote a piece for the Financial Times that heavily quotes a 1990 paper by an economist named Rebecca Henderson titled "Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms." The paper outlines how the organizational structure of companies can prevent them from innovating in specific ways. Most specifically the paper describes the kind of innovation that keeps the shape of the previous generation's product, but completely rewires it: Think film cameras to digital or the Walkman to MP3 players. Here's Harford describing the idea:

As you see at the bottom of the framework you have option three: "Strategic mirror-breaking." This is also sometimes called an "inverse Conway maneuver" in software engineering circles: An approach where you actually adjust your organizational model in order to change the way your systems are architected.5 Basically you attempt to outline the type of system design you want (most of the time it's about more modularity) and you back into an org structure that looks like that.

In case it seems like all this might be academic, the architecture of organizations has been shown to have a fundamental on the company's ability to innovate. Tim Harford recently wrote a piece for the Financial Times that heavily quotes a 1990 paper by an economist named Rebecca Henderson titled "Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms." The paper outlines how the organizational structure of companies can prevent them from innovating in specific ways. Most specifically the paper describes the kind of innovation that keeps the shape of the previous generation's product, but completely rewires it: Think film cameras to digital or the Walkman to MP3 players. Here's Harford describing the idea:

Credit: Organizational Charts by Manu CornetI first ran into Conway's Law while helping a brand redesign their website. The client, a large consumer electronics company, was insistent that the navigation must offer three options: Shop, Learn, and Support. I valiantly tried to convince them that nobody shopping on the web, or anywhere else, thought about the distinction between shopping and learning, but they remained steadfast in their insistence. What I eventually came to understand is that their stance wasn't born out of customer need or insight, but rather their own organizational chart, which shockingly included a sales department, a marketing department, and a support department.

"Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." That's the way computer scientist and software engineer Melvin Conway put it in a 1968 paper titled "How Do Committees Invent?" His point was that the choices we make before start designing any system most often fundamentally shapes the final output.1 Or, as he put it, "the very act of organizing a design team means that certain design decisions have already been made."

Why does this happen, where does it happen, and what can we do about it? That's the goal of this essay, but before I get there we've got to take a short sojourn into the history of the concept. As I mentioned, the idea in its current form came from Melvin Conway in May of 1968. In the article he cited a few key sources as inspiration including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and historian C. Northcote Parkinson, who's 1957 book Parkinson's Law and Other Studies in Administration was particularly influential in spelling out the ever-increasing complexity that any bureaucratic organization will create.2 Finally, judging by the focus on modularity in Conway's writing, it seems clear he was also inspired by Herbert Simon's work, in particular his "Architecture of Complexity" paper and the Parable of Two Watchmakers (which I wrote about earlier).

Parkinson aside (who did so mostly in jest), very few have the chutzpah to actually name a law after themselves and Conway wasn't responsible for the law's coining. That came a few months after the "Committees" article was published from a fan and fellow computer scientist George Mealy. In his paper for the July 1968 National Symposium on Modular Programming (which I seem to be one of the very few people to have actually tracked down), Mealy examined four bits of "conventional wisdom" that surrounded the development of software systems at the time. Number four came directly from Conway: "Systems resemble the organizations that produced them." The naming comes 3 pages in:

Credit: Organizational Charts by Manu CornetI first ran into Conway's Law while helping a brand redesign their website. The client, a large consumer electronics company, was insistent that the navigation must offer three options: Shop, Learn, and Support. I valiantly tried to convince them that nobody shopping on the web, or anywhere else, thought about the distinction between shopping and learning, but they remained steadfast in their insistence. What I eventually came to understand is that their stance wasn't born out of customer need or insight, but rather their own organizational chart, which shockingly included a sales department, a marketing department, and a support department.

"Organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations." That's the way computer scientist and software engineer Melvin Conway put it in a 1968 paper titled "How Do Committees Invent?" His point was that the choices we make before start designing any system most often fundamentally shapes the final output.1 Or, as he put it, "the very act of organizing a design team means that certain design decisions have already been made."

Why does this happen, where does it happen, and what can we do about it? That's the goal of this essay, but before I get there we've got to take a short sojourn into the history of the concept. As I mentioned, the idea in its current form came from Melvin Conway in May of 1968. In the article he cited a few key sources as inspiration including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and historian C. Northcote Parkinson, who's 1957 book Parkinson's Law and Other Studies in Administration was particularly influential in spelling out the ever-increasing complexity that any bureaucratic organization will create.2 Finally, judging by the focus on modularity in Conway's writing, it seems clear he was also inspired by Herbert Simon's work, in particular his "Architecture of Complexity" paper and the Parable of Two Watchmakers (which I wrote about earlier).

Parkinson aside (who did so mostly in jest), very few have the chutzpah to actually name a law after themselves and Conway wasn't responsible for the law's coining. That came a few months after the "Committees" article was published from a fan and fellow computer scientist George Mealy. In his paper for the July 1968 National Symposium on Modular Programming (which I seem to be one of the very few people to have actually tracked down), Mealy examined four bits of "conventional wisdom" that surrounded the development of software systems at the time. Number four came directly from Conway: "Systems resemble the organizations that produced them." The naming comes 3 pages in:

Our third aphorism-"if one programmer can do it in one year, two programmers can do it in two years"-is merely a reflection of the great difficulty of communication in a large organization. The crux of the problem of giganticism [sic] and system fiasco really lies in the fourth dogma. This -- "systems resemble the organizations that produced them" -- has been noticed by some of us previously, but it appears not to have received public expression prior to the appearance of Dr. Melvin E. Conway's penetrating article in the April 1968 issue of Datamation. The article was entitled "How Do Committees Invent?". I propose to call my preceding paraphrase of the gist of Conway's paper "Conway's Law".While most, including Conway on his own website, credit Fred Brooks' 1975 Mythical Man Month with naming the law, it seems that Mealy deserves the credit (though Brooks' book is surely the reason so many know about Conway's important concept).3Back to the questions at hand: Why does this happen, where does it happen, and what can we do about it? Let's start with the why. This seems like it should be easy to answer, but it's actually not. The answer starts with some basics of hierarchy and modularity that Herbert Simon offered up in his Parable of Two Watchmakers: Mainly, breaking a system down into sets of modular subsystems seems to be the most efficient design approach in both nature and organizations. For that reason we tend to see companies made up of teams which are then made up of more teams and so-on. But that still doesn't answer the question of why they tend to design systems in their image. To answer that we turn to some of the more recent research around the "mirroring hypothesis," which (in simplified terms) is an attempt to prove out Conway's Law. Carliss Baldwin, a professor at Harvard Business School, seems to be spearheading much of this work and has been an author on two of the key papers on the subject. Most recently, "The mirroring hypothesis: theory, evidence, and exceptions" is a treasure trove of information and citations. Her theory as to why mirroring occurs is essentially that it makes life easier for everyone who works at the company:

The mirroring of technical dependencies and organizational ties can be explained as an approach to organizational problem-solving that conserves scarce cognitive resources. People charged with implementing complex projects or processes are inevitably faced with interdependencies that create technical problems and conflicts in real time. They must arrive at solutions that take account of the technical constraints; hence, they must communicate with one another and cooperate to solve their problems. Communication channels, collocation, and employment relations are organizational ties that support communication and cooperation between individuals, and thus, we should expect to see a very close relationship—technically a homomorphism—between a network graph of technical dependencies within a complex system and network graphs of organizational ties showing communication channels, collocation, and employment relations.It's all still a bit circular, but the argument that in most cases a mirrored product is both reasonably optimal from a design perspective (since organizations are structured with hierarchy and modularity) and also cuts down the cognitive load by making it easy for everyone to understand (because it works like an org they already understand) seems like a reasonable one.4 The paper then goes on to survey the research to understand what kind of industries mirroring is most likely to occur and the answer seems to be everywhere. They found evidence from across expected places like software and semiconductors, but also automotive, defense, sports, and even banking and construction. For what it's worth, I've also seen it across industries in marketing projects throughout my own career. That's the why and the where, which only leaves us with the question of what an organization can do about it. Here there seem to be a few different approaches. The first one is to do nothing. After all, it may well be the best way to design a system for that organization/problem. The second is to find an appropriate balance. If you buy the idea that some part of mirroring/Conway's Law is simply about making it easier to understand and maintain systems, than its probably good to keep some mirroring. But it doesn't need to be all or nothing. In the aforementioned paper, Baldwin and her co-authors have a nice little framework for thinking about different approaches to mirroring depending on the kind of business:

As you see at the bottom of the framework you have option three: "Strategic mirror-breaking." This is also sometimes called an "inverse Conway maneuver" in software engineering circles: An approach where you actually adjust your organizational model in order to change the way your systems are architected.5 Basically you attempt to outline the type of system design you want (most of the time it's about more modularity) and you back into an org structure that looks like that.

In case it seems like all this might be academic, the architecture of organizations has been shown to have a fundamental on the company's ability to innovate. Tim Harford recently wrote a piece for the Financial Times that heavily quotes a 1990 paper by an economist named Rebecca Henderson titled "Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms." The paper outlines how the organizational structure of companies can prevent them from innovating in specific ways. Most specifically the paper describes the kind of innovation that keeps the shape of the previous generation's product, but completely rewires it: Think film cameras to digital or the Walkman to MP3 players. Here's Harford describing the idea:

As you see at the bottom of the framework you have option three: "Strategic mirror-breaking." This is also sometimes called an "inverse Conway maneuver" in software engineering circles: An approach where you actually adjust your organizational model in order to change the way your systems are architected.5 Basically you attempt to outline the type of system design you want (most of the time it's about more modularity) and you back into an org structure that looks like that.

In case it seems like all this might be academic, the architecture of organizations has been shown to have a fundamental on the company's ability to innovate. Tim Harford recently wrote a piece for the Financial Times that heavily quotes a 1990 paper by an economist named Rebecca Henderson titled "Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms." The paper outlines how the organizational structure of companies can prevent them from innovating in specific ways. Most specifically the paper describes the kind of innovation that keeps the shape of the previous generation's product, but completely rewires it: Think film cameras to digital or the Walkman to MP3 players. Here's Harford describing the idea:

Dominant organisations are prone to stumble when the new technology requires a new organisational structure. An innovation might be radical but, if it fits the structure that already existed, an incumbent firm has a good chance of carrying its lead from the old world to the new. A case study co-authored by Henderson describes the PC division as "smothered by support from the parent company". Eventually, the IBM PC business was sold off to a Chinese company, Lenovo. What had flummoxed IBM was not the pace of technological change — it had long coped with that — but the fact that its old organisational structures had ceased to be an advantage. Rather than talk of radical or disruptive innovations, Henderson and Clark used the term "architectural innovation".Like I said before, it's all quite circular. It's a bit like the famous quote "We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us." Companies organize themselves and in turn design systems that mirror those organizations which in turn further solidify the organizational structure that was first put in place. Conway's Law is more guiding principle than physical property, but it's a good model to keep in your head as you're designing organizations or systems (or trying to disentangle them). Footnotes:

- He was writing mostly about software systems, but as you'll see it's much more broadly applicable.↑

- Here's how Conway explains Parkinson's complexity concept: "As each new brand is created it justifies itself by challenging the established order. Thus, after a while, the organization is fully occupied in internal political warfare."↑

- As an aside, it's hard not to think that Mealy's third point about what one programmer can do versus two sounds a lot like Fred Brooks' "mythical man month" concept. Mealy worked with Brooks on OS/360 and in the book Computer Pioneers by J.A.N. Lee it's mentioned that Mealy's Law was also named at the 1968 symposium: "There is an incremental programmer who, when added to a project, consumes more resources than are made available." Sounds pretty similar to me.↑

- There's a very interesting point about the role of "information hiding" in pushing companies into Conway's Law. Essentially the idea is that companies naturally hide information within teams or departments for the sake of simplicity across the rest of the company. It would only make things more complicated, for instance, if the finance team exposed the detailed rules of GAAP accounting instead of just distributing a monthly GAAP accounting report. "Information hiding as a means of controlling complexity is a fundamental principle underlying the mirroring hypothesis. With information hiding, each module in a technical system is informationally isolated from other modules within a framework of system design rules. This means that independent individuals, teams, or firms can work separately on different modules, yet the modules will work together as a whole (Baldwin and Clark, 2000)."↑

- If you're interested in the idea you should check out the episode of Software Engineering Radio with engineering leader Kevin Goldsmith.↑

- Arrow, K. J. (1985). Informational structure of the firm. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 303-307.

- Brunton-spall, Michael (2 Nov. 2015.). The Inverse Conway Manoeuvre and Security – Michael Brunton-Spall – Medium. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@bruntonspall/the-inverse-conway-manoeuvre-and-security-55ee11e8c3a9

- Colfer, L. J., & Baldwin, C. Y. (2016). The mirroring hypothesis: theory, evidence, and exceptions. Industrial and Corporate Change, 25(5), 709-738.

- Conway, Melvin E. "How do committees invent." Datamation 14.4 (1968): 28-31.

- Conway, Melvin E. "The Tower of Babel and the Fighter Plane." Retrieved from http://melconway.com/keynote/Presentation.pdf

- Evans, Benedict (31 Aug. 2018.). Tesla, software and disruption. Benedict Evans. Retrieved from https://www.ben-evans.com/benedictevans/2018/8/29/tesla-software-and-disruption

- Galbraith, J. K. (2001). The essential galbraith. HMH.

- Harford, Tim. (6 Sept. 2018.). Why big companies squander good ideas. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/3c1ab748-b09b-11e8-8d14-6f049d06439c

- Henderson, R. M., & Clark, K. B. (1990). Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Administrative science quarterly, 9-30.

- Hvatum, L. B., & Kelly, A. (2005). What do I think about Conway's Law now?. In EuroPLoP (pp. 735-750).

- Lee, J. A. (1995). International biographical dictionary of computer pioneers. Taylor & Francis.

- MacCormack, A., Baldwin, C., & Rusnak, J. (2012). Exploring the duality between product and organizational architectures: A test of the "mirroring" hypothesis. Research Policy, 41(8), 1309-1324.

- MacDuffie, J. P. (2013). Modularity‐as‐property, modularization‐as‐process, and ‘modularity'‐as‐frame: Lessons from product architecture initiatives in the global automotive industry. Global Strategy Journal, 3(1), 8-40.

- Mealy, George, "How to Design Modular (Software) Systems," Proc. Nat'l. Symp. Modular Programming, Information & Systems Institute, July 1968.

- Newman, Sam. (30 Jun. 2014.). Demystifying Conway's Law. ThoughtWorks. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtworks.com/insights/blog/demystifying-conways-law

- Parnas, D. L. (1972). On the criteria to be used in decomposing systems into modules. Communications of the ACM, 15(12), 1053-1058.

- Software Engineering Radio. Kevin Goldsmith on Architecture and Organizational Design : Software Engineering Radio. Se-radio.net. Retrieved from http://www.se-radio.net/2018/07/se-radio-episode-331-kevin-goldsmith-on-architecture-and-organizational-design/

- Van Dusen, Matthew (19 May 2016.). A principle called "Conway's Law" reveals a glaring, biased flaw in our technology. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/687457/a-principle-called-conways-law-reveals-a-glaring-biased-flaw-in-our-technology/