Known Unknowns [Framework of the Day]

Donald Rumsfeld's 'Known Unknowns' framework and its application outside of politics.

As some of you may know I’ve been collecting mental models and working on a book for a little while now (it’s been going pretty slow since my daughter was born in January). This is more notes than chapter, but I still thought it was worth sharing. If you like this I’m happy to do more in the future (I wrote about the pace layers framework in my last post). Oh, and if you haven’t already, sign up to get my new blog posts by email, it’s the best way to keep up.

By all accounts Donald Rumsfeld was a man who didn’t suffer from a shortage of self-confidence. Whether it was Meet the Press, Errol Morris’s documentary Unknown Known (it's also worth reading the four-part series Morris wrote on Rumsfeld/the documentary for the New York Times), or a grilling from Jon Stewart on the Daily Show, he always seemed supremely satisfied with his own certainty. Which must have made the public response to what’s become his most famous comment all the more vexing. At a Department of Defense briefing in February, 2002, then Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was asked about evidence to support claims of Iraq helping to supply terrorist organizations with weapons of mass destruction. "Because," the questioner explained, "there are reports that there is no evidence of a direct link between Baghdad and some of these terrorist organizations."

Rumsfeld famously replied:

(Give the whole article from the Project Management Institute on how to apply known unknowns to project management a read.)

Rumsfeld went on to title his memoir Known and Unknown, and explained his perspective on its meaning early in the book:

(Give the whole article from the Project Management Institute on how to apply known unknowns to project management a read.)

Rumsfeld went on to title his memoir Known and Unknown, and explained his perspective on its meaning early in the book:

Despite the context for the original quote, the idea is a useful way to think about strategy and understand the various risks you might face.

Despite the context for the original quote, the idea is a useful way to think about strategy and understand the various risks you might face.

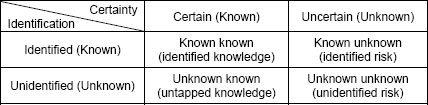

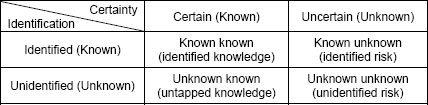

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.While it’s a mouthful and the context shouldn’t be lost, there’s a useful framework buried in Rumsfeld’s dodge. It looks something like this:

(Give the whole article from the Project Management Institute on how to apply known unknowns to project management a read.)

Rumsfeld went on to title his memoir Known and Unknown, and explained his perspective on its meaning early in the book:

(Give the whole article from the Project Management Institute on how to apply known unknowns to project management a read.)

Rumsfeld went on to title his memoir Known and Unknown, and explained his perspective on its meaning early in the book:

At first glance, the logic may seem obscure. But behind the enigmatic language is a simple truth about knowledge: There are many things of which we are completely unaware—in fact, there are things of which we are so unaware, we don’t even know we are unaware of them. Known knowns are facts, rules, and laws that we know with certainty. We know, for example, that gravity is what makes an object fall to the ground. Known unknowns are gaps in our knowledge, but they are gaps that we know exist. We know, for example, that we don’t know the exact extent of Iran’s nuclear weapons program. If we ask the right questions we can potentially fill this gap in our knowledge, eventually making it a known known. The category of unknown unknowns is the most difficult to grasp. They are gaps in our knowledge, but gaps that we don’t know exist. Genuine surprises tend to arise out of this category. Nineteen hijackers using commercial airliners as guided missiles to incinerate three thousand men, women, and children was perhaps the most horrific single unknown unknown America has experienced.Rumsfeld was obsessed with Pearl Harbor. In his memoir he quotes a foreword written by game theorist/nuclear strategist Thomas Schelling that introduced a book about the attack by Roberta Wohlstetter. Schelling wrote (emphasis mine):

If we think of the entire U.S. government and its far-flung military and diplomatic establishment, it is not true that we were caught napping at the time of Pearl Harbor. Rarely has a government been more expectant. We just expected wrong. And it was not our warning that was most at fault, but our strategic analysis. We were so busy thinking through some “obvious” Japanese moves that we neglected to hedge against the choice that they actually made. And it was an "improbable" choice; had we escaped surprise, we might still have been mildly astonished. (Had we not provided the target, though, the attack would have been called off.) But it was not all that improbable. If Pearl Harbor was a long shot for the Japanese, so was war with the United States; assuming the decision on war, the attack hardly appears reckless. There is a tendency in our planning to confuse the unfamiliar with the improbable. The contingency we have not considered seriously looks strange; what looks strange is thought improbable; what is improbable need not be considered seriously.In other words, unknown unknowns. Outside of politics, the framework is a useful way to categorize risk/uncertainty in life or business. I got interested and dug around a bit to find the historical context for the idea, which led me in a few different directions. Rumsfeld credits William R. Graham at NASA with first introducing him to the concept in the late-90s, though it turns out to go back a lot further than that. The oldest reference I could find comes from a 1968 issue of the Armed Forces Journal International. In the article "The 'Known Unknowns' And The 'Unknown Unknowns'" about the procurement of new weapons. The article opens like this:

Cheyenne was the first major Army weapon to be developed under DoD’s sometimes controversial contract definition procedures. General Bunker put the process in perspective by pointing out that no procedural system can entirely eliminate "surprises" from happening during development of a complex weapons system, and that contract definition wasn’t expected to. "But," he pointed out, "there are two kinds of technical problems: there are the known unknowns, and the unknown unknowns. Contract definition has helped eliminate the known unknowns. It cannot eliminate completely potential cost overruns, because these are due largely to the unknown unknowns."The term pops up throughout the 70s in relation to military procurement. Sometime in there some folks also start using the term "unk-unks" to refer to the most dangerous of the four boxes. Here it is in context from a 1982 New Yorker piece on the airplane industry:

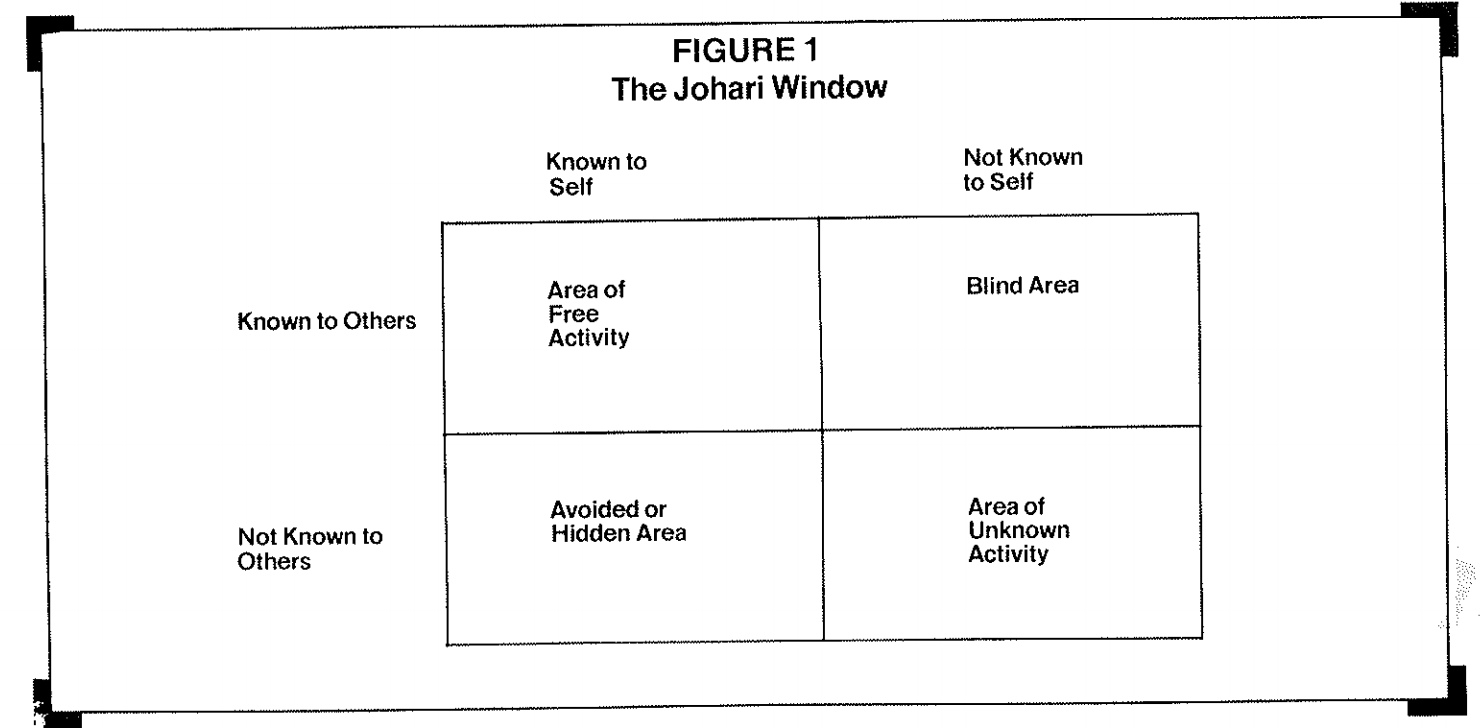

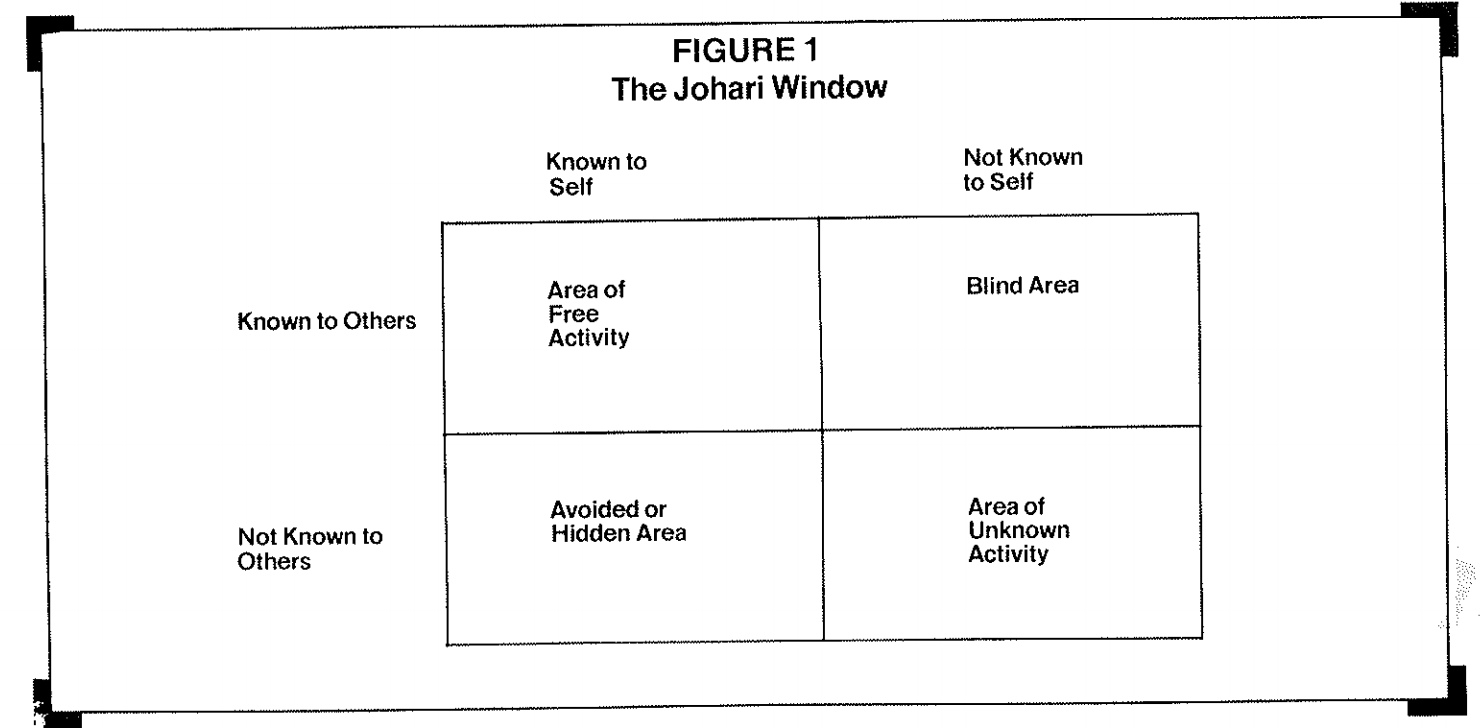

The excitement of this business lies in the sweep of the uncertainties. Matters as basic as the cost of the product -- the airplane -- and its break-even point are obscure because so much else is uncertain or unclear. The fragility of the airline industry does, of course, create uncertainties about the size and the reliability of the market for a new airplane or a new variant of an existing airplane. Then, there is a wide range of unknowns, for which an arbitrarily fixed amount of money must be set aside in the development budget. Some of these are so-called known unknowns; others are thought of as unknown unknowns and are called "unk-unks." The assumption is that normal improvements in an airplane program or an engine program will create problems of a familiar kind that add to the costs; these are the known unknowns. The term "unk-unks" is used to cover less predictable contingencies; the assumption is that any new airplane or engine intended to advance the state of the art will harbor surprises in the form of problems that are wholly unforeseen, and perhaps even novel, and these must be taken account of in the budget.Some are even trying to use it as a kind of code word for breakthrough innovations. Finally, although it's not clear they're connected, there's a very similar framework from psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham from 1955 called the Johari Window. The model attempts to visualize the effects of our knowledge of self and how that works in relation to the knowledge of others:

Quadrant I, the area of free activity, refers to behavior and motivation known to self and known to others. Quadrant II, the blind area, where others can see things in ourselves of which we are unaware. Quadrant III, the avoided or hidden area, represents things we know but do not reveal to others (e.g, a hidden agenda or matters about which we have sensitive feelings) Quadrant IV, area of unknown activity. Neither the individual nor others are aware of certain behaviors or motives: Yet we can assume their existence because eventually some of these things become known, and it motives were influencing relationships all along.

Despite the context for the original quote, the idea is a useful way to think about strategy and understand the various risks you might face.

Despite the context for the original quote, the idea is a useful way to think about strategy and understand the various risks you might face.

Bibliography:

- Andrews, Walter. (1968). The "Known Uknnowns" And The "Unknown Unknowns". Armed Forces Journal, p. 14-15.

- BBC NEWS | Magazine | What we know about 'unknown unknowns'. (2018). News.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/7121136.stm

- Defense.gov Transcript: DoD News Briefing - Secretary Rumsfeld and Gen. Myers . (2002). Archive.defense.gov. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from http://archive.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=2636

- Graham, D. (2014). Rumsfeld's Knowns and Unknowns: The Intellectual History of a Quip. The Atlantic. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/03/rumsfelds-knowns-and-unknowns-the-intellectual-history-of-a-quip/359719/

- Hevesi, D. (2015). Roberta Wohlstetter, 94, Military Policy Analyst, Dies. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/11/obituaries/11wohlstetter.html

- Kim, S. D. (2012). Characterizing unknown unknowns. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2012—North America, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Kirkpatrick, L.B. Book review of Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision by Roberta Wohlstetter — Central Intelligence Agency. (1993). Cia.gov. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol7no3/html/v07i3a13p_0001.htm

- Grimes, W. (2016). Thomas C. Schelling, Master Theorist of Nuclear Strategy, Dies at 95. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/business/economy/thomas-schelling-dead-nobel-laureate.html

- Luft, Joseph, and Harry Ingham. "The johari window." Human Relations Training News 5.1 (1961): 6-7.

- Morris, E. (2014). The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld (Part 1). Opinionator. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/25/the-certainty-of-donald-rumsfeld-part-1/

- Morris, E. (2014). The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld (Part 2). Opinionator. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/26/the-certainty-of-donald-rumsfeld-part-2/

- Morris, E. (2014). The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld (Part 3). Opinionator. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/27/the-certainty-of-donald-rumsfeld-part-3/

- Morris, E. (2014). The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld (Part 4). Opinionator. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/28/the-certainty-of-donald-rumsfeld-part-4/

- Mullins, J. W. (2007). Discovering" Unk-Unks". MIT Sloan Management Review, 48(4), 17.

- Newhouse, J. (1982). A sporty game: I. betting the Company. The New Yorker, 48-105.

- Ramasesh, R. V., & Browning, T. R. (2014). A conceptual framework for tackling knowable unknown unknowns in project management. Journal of Operations Management, 32(4), 190-204.

- Rumsfeld, D. (2011). Known and unknown: a memoir. Penguin.

- Schelling, Thomas C. "Meteors, Mischief, and War." Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 16.7 (1960): 292-300.

- Steyn, M. (2003). Rummy speaks the truth, not gobbledygook. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/personal-view/3599959/Rummy-speaks-the-truth-not-gobbledygook.html

-

The unknown unknowns. Telecommunications: A Survey. (1985, November 23). Economist, p. 40. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.galegroup.com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/tinyurl/78pi57

- Wilson, George C. (1969). The Washington Post, p. A1.

- Wohlstetter, Roberta. Pearl Harbor: warning and decision. Stanford University Press, 1962.

- Wright, Robert A. (1970). Lockheed's Illness Is Contagious. New York Times.